By Diane Titche and Ellin Oliver Keene

Diane Titche

Walking into a 3rd-grade classroom, a principal observes students seated at their desks. Nearly all eyes are on the teacher as she points out information on a website projected on the whiteboard. The teacher poses a question, and hands fly up. “Turn and talk to your neighbor,” the teacher says, “and be prepared to share your answer.” The principal walks around and notices that all the students are talking with a partner about the teacher’s question. After a brief period, the teacher calls for the students’ attention, and they all turn back to face her. Several hands go up and each student the teacher calls on shares their answer to the teacher’s question. The teacher acknowledges each response with a brief, “Thank you for sharing,” and moves on to another student. The principal makes a note and moves on to the next classroom.

“Wow!” the principal tells her later. “I love seeing how engaged your students are when I visit your classroom!”

Are the students in this classroom engaged? How can we tell? As educators, how do we define student engagement, and more importantly, what are the steps we can take to ensure more of our students are engaged more of the time?

The example above was from Diane’s 3rd-grade classroom. She prided herself on carefully planning her lessons to give all students plenty of opportunities to think, talk, and share. Her students responded with plenty of active participation, and she took that to mean they were engaged.

Yet there was something that nagged at her. There were times in her classroom when it seemed her students were truly on fire with their learning, and as a result, she was on fire with her teaching. Those times made her wonder, “What’s different here? If this is true engagement, what’s happening with my kids all those other times, and how do I get my students to engage in their learning more often?”

Those questions stuck with Diane, and she began to expand her thinking with Ellin Keene’s book, “Engaging Children: Igniting a Drive for Deeper Learning.” There she learned we can teach our students what engagement is and how to recognize when they are engaged. She realized that ultimately, responsibility for our students’ engagement rests with them.

Ignite Engagement Initiative

Ellin Oliver Keene

As an Early Literacy Coach for Kent Intermediate School District, Diane set out to share her new insights with the teachers and coaches she supports, and an initiative known as Ignite Engagement was born. This long-term professional development initiative is now entering its third year. In partnership with Ellin Keene, Ignite Engagement has focused on the questions:

- How do we support students in learning how to engage?

- How do we create the conditions to ensure true engagement happens more often in our classrooms?

- In what ways might we help students learn to re-engage when they realize that they’re not engaged?

The Ignite Engagement initiative consists of cohorts of teacher and coach partnerships and three administrators representing different K-8 grade levels in different districts. Members were selected through an application process, as Diane and Ellin wanted educators who were open to trying new practices, exploring questions of engagement together with their students, and were willing to work in a highly collaborative environment with other cohort members.

The cohorts explore deeply what it means to be engaged themselves and what conditions appear to facilitate student engagement. They meet together every month, and spend time in classrooms with Ellin and Diane, observing and studying students and having conversations about what engages them in school and why.

Understanding Engagement

In order to better understand the concept of engagement, cohort members began by examining their own stories of engagement. They reflected on times in their lives when they were deeply engaged in something – personally or professionally. They examined their thoughts, feelings, actions, and reactions during those times, and constructed their own definitions of engagement.

The next step was to share their own engaged stories and the stories of other engaged people with their students. They asked them to identify the characteristics of engaged people and look for the characteristics nearly every story had in common.

In “Engaging Children” (2018) Ellin undertook research in classrooms around the country and asked children to characterize what they experience when they are engaged. After culling through hundreds of responses, she uncovered four patterns that characterized engagement for many of the students. She refers to these patterns as the pillars of engagement. They are:

| Pillars of Engagement | What a child might say or show. | Definition |

| Intellectual Urgency | “I have to know more” | Students are willing to put time and considerable effort into learning more. They drive the learning with their own questions. |

| Emotional Resonance | “I react to an idea and get into it with my heart as well as my mind” | Engaged students can describe experiences when a concept is imprinted in the heart as well as the mind. |

| Perspective Bending | “Other learners affect my thinking and beliefs. I affect theirs.” | Engaged students are aware of how others’ knowledge, emotions, and beliefs shape their own. They enjoy engaging in debate and civil arguments. |

| The Aesthetic World | “This (book or idea or experience) is so cool. It’s mine and I’m drawn to it. It feels like it was created just for me. It’s beautiful or hilarious or amazing.” | Engaged students describe moments when they find something beautiful or extraordinary, captivating, hilarious, or unusually meaningful. They may speak of a book or illustration, a painting or idea in science or math that seems to have been created just for them. |

In her research, Elin found that most engaged stories, descriptions of true engagement, include one or more of the pillars. She found that it is highly effective to share this language with students so they have an ongoing, working discourse they can use to discuss engagement. As students become more familiar with these descriptors of engagement, they become more aware of their own engagement and feel greater control over it. Ellin argues in the book that it is not up to the teacher to engage students. Teachers can share their own stories of engagement, create the classroom conditions that are conducive to engagement, and ensure there is ongoing discourse about engagement but, in the end, students need to gradually assume responsibility, much of the time, for their own engagement.

The Ignite Engagement cohort teachers built on these ideas by asking students to share their stories of engagement and to identify which of the Four Pillars their stories most exemplified. Students shared stories of learning to play an instrument, creating computer games through coding, making things out of recyclables, playing with friends, traveling with family, reading quietly in their room, drawing and painting…the list goes on. The teachers also asked them to begin thinking about and evaluating their level of engagement in various lessons and activities throughout the school day.

Back in the cohort meetings, the members discussed the kids’ stories. They noticed one startling pattern in nearly all the stories shared…those times when their students were highly engaged were almost always outside of academic settings. That led them to explore the questions, what are the conditions when our students are truly engaged, and how do we recreate those conditions in our classrooms?

Conditions for Engagement

Conditions for Engagement

In Ellin’s book, “Engaging Children: Igniting a Drive for Deeper Learning”, she identifies many of those conditions. In the monthly cohort meetings, members study and discuss those conditions, share ways each teacher is working to recreate those conditions, and explore how to best respond when they observe signs of deep engagement in their students. Some examples of the conditions that increase the likelihood students will choose to engage at high levels include:

- Classroom Environment Conditions

- The classroom is arranged with clearly delineated areas for individual, partner, and group work.

- Students are able to choose areas to work where they can be most productive.

- Students help arrange the classroom library so they are familiar with the selection of books and are able to easily access and return books they want to read.

- Classroom Climate Conditions

- There is an atmosphere of openness and trust between all members of the classroom community.

- There is a sense of pride and respect for the space that members of the classroom community inhabit.

- Activities convey a sense of purpose and children seek to reflect on and discuss ideas of great import.

- Teacher Practice Conditions

- The teacher is the lead learner, modeling what learners think about in order to understand with greater insight.

- The teacher provides frequent opportunities for students to collaborate with each other.

- The teacher raises social justice and equity issues from the world outside the classroom, helps students read and talk about them, and supports students to take action to mitigate conflict in the world.

Into the Classroom

These examples from Ignite Engagement Cohort teachers highlight the different ways teachers and coaches are working together to create the conditions conducive to engagement in their classrooms.

Christy Gast and Bridget Rieth, who teach fourth and fifth grade respectively, spend time with their students throughout the year discussing and exploring what it means to be engaged. They share their own stories of engagement, explore the lives of highly engaged individuals through narrative and informational texts, and work to develop a deep understanding of each of the four pillars of engagement. They pause to recognize and celebrate when students in the classroom are highly engaged in their learning. All this focus on engagement has led to students’ agency: they are able to identify their own levels of engagement and can work independently to re-engage when their energy wanes.

Tammy Singleton, a third-grade teacher, has changed her teaching practice to incorporate much more time for one-on-one conferences with students. She maintained that practice while teaching remotely in the 2020-2021 school year. Her conferences are focused on students’ growing literacy skills and on each student’s engagement. Tammy helps them develop the skills to monitor their own levels of engagement and develop strategies for re-engaging when needed. And the impact on the students? They are more excited about reading, are reading more, are eager to talk with other readers, and are growing at faster rates in their daily classroom work and assessments than in previous years. They recognize when a book or a topic is engaging them and when it’s not and have strategies to increase their own engagement levels without Tammy’s assistance.

Jenn Kidd, who teaches fourth grade, has transformed her literacy block from a traditional worksheet and leveled guided reading group focus to an authentic Reader’s Workshop, where her students choose what to read, have long, uninterrupted periods of time to read and write and have opportunities to talk with classmates and Jenn about their reading. Jenn says, “We got into this profession because we are fascinated by kids. They inspire us and we want to keep inspiring them. In my old model of teaching, there was so much weighing down on me because I was so focused on the curriculum and testing. I started to lose the joy in teaching. In order to create the space for students to find and explore their passions, I had to transition my literacy block into an authentic Reader’s Workshop and let go of some of the control I always thought I needed to have. I’ve seen a huge difference in how much my kids read, their desire to read, and how engaged they are during workshop time. I don’t have to redirect kids anywhere near as often, which gives me more time for one-on-one conferences with my kids and building truly meaningful relationships with them. This work has renewed my joy for teaching.”

Sherry Kilpatrick, a fourth-grade teacher, is introducing more opportunities for student-driven inquiry into her classroom. This began with a spontaneous burst of questions from her students about a read-aloud she was sharing with them. Sherry didn’t know the answers, but instead of putting them off until later, she encouraged her students to explore their questions- right then and there! The kids were so excited to be given this time to dig into finding answers to the questions they generated. Before they knew it, they had spent nearly an hour finding answers to their initial questions, generating new questions, and continuing to enhance their understanding of the setting in the book. In that hour, Sherry realized the power of student-generated questions, student choice, and inquiry in helping her students truly engage in their learning. Now she plans to give her students more regular opportunities for choice and inquiry and continues to watch for those spontaneous moments so she can capitalize on them. Sherry’s joy is evident when she shares,

“The kids always take me on adventures. I don’t always know where it’s going, but they are excited, they are learning, and they are doing better work than I’ve seen in the past. At parent-teacher conferences, my students’ parents share with me how excited they are about what they see their children doing and learning.”

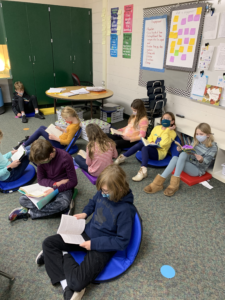

There are many other ways the Ignite Engagement Cohort teachers and coaches are working together to implement the conditions that lead to higher levels of student engagement in their classrooms. These include offering plenty of flexible seating, modeling how to manage struggle and increasing the level of challenge they offer their students, spending more time teaching about historical and current world issues (especially the controversial ones so prevalent in our daily news), and giving their students plenty of choice. Without exception, the teachers have a renewed sense of joy in their teaching. They notice a greater understanding of community with their students, increased engagement, and improved academic outcomes since initiating their work on engagement.

***

If Diane were to return to her third-grade classroom today, she would know it’s not enough to garner students’ participation. She would understand they need to engage in and take responsibility for their own engagement, and it’s her responsibility to create the conditions that support deep engagement. The current cohort members will continue delving deeper into the conditions that lead to high levels of engagement and expanding on the practices they’ve already embraced. In the 2021-2022, school year Ignite Engagement will welcome a new cohort of teachers and coaches to begin their exploration into “Engaging Children.” Their creativity, energy, and insights will help all involved in the program continue to grow in their understanding of exactly what it takes to help students engage in their learning at the highest levels. When that happens, students will carry forward what they learn, be able to apply their learning in new circumstances, and grow into the thoughtful, respectful, and responsible individuals we all want our students to become. And isn’t that why we teach?

Bibliography

Keene, E. O. (2018). Engaging Children: Igniting a Drive for Deeper Learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Author Bios:

Diane Titche has been an elementary classroom teacher, instructional coach, and is currently an Early Literacy Coach with Kent Intermediate School District in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Previous publications include an article in and a section in Comprehension and Collaboration, First Edition, by Harvey Daniels and Stephanie Harvey. She is the founder and facilitator of the Ignite Engagement initiative..

Ellin Oliver Keene has been a classroom teacher, staff developer, non-profit director and adjunct professor of reading and writing. Ellin consults with schools and districts internationally and is the author or co-author of 7 books, including Mosaic of Thought, The power of comprehension strategy instruction (2008) and Engaging Children: Igniting the drive for deeper learning (2018). Ellin is currently at work on The Literacy Studio focused on an up-to-date conceptualization of Readers/Writers’ workshop.

Manuscript word count (including references and bios): 2639